Friedmann equations

| Physical cosmology |

|---|

| Universe · Big Bang Age of the universe Timeline of the Big Bang Ultimate fate of the universe |

|

Early universe

|

|

Expanding universe

|

|

Components

|

The Friedmann equations are a set of equations in physical cosmology that govern the expansion of space in homogeneous and isotropic models of the universe within the context of general relativity. They were first derived by Alexander Friedmann in 1922[1] from Einstein's field equations of gravitation for the Friedmann-Lemaître-Robertson-Walker metric and a fluid with a given mass density  and pressure

and pressure  . The equations for negative spatial curvature were given by Friedmann in 1924.[2]

. The equations for negative spatial curvature were given by Friedmann in 1924.[2]

Contents |

Assumptions

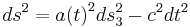

The Friedmann equations start with the simplifying assumption that the universe is spatially homogeneous and isotropic, i.e. the Cosmological Principle; empirically, this is justified on scales larger than ~100 Mpc. The Cosmological Principle implies that the metric of the universe must be of the form:

where  is a three dimensional metric that must be one of (a) flat space, (b) a sphere of constant positive curvature or (c) a hyperbolic space with constant negative curvature. The parameter

is a three dimensional metric that must be one of (a) flat space, (b) a sphere of constant positive curvature or (c) a hyperbolic space with constant negative curvature. The parameter  discussed below takes the value 0, 1, -1 in these three cases respectively. It is this fact that allows us to sensibly speak of a "scale factor",

discussed below takes the value 0, 1, -1 in these three cases respectively. It is this fact that allows us to sensibly speak of a "scale factor",  .

.

Einstein's equations now relate the evolution of this scale factor to the pressure and energy of the matter in the universe. The resulting equations are described below.

The equations

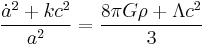

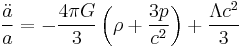

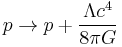

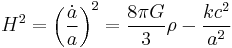

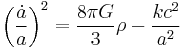

There are two independent Friedmann equations for modeling a homogeneous, isotropic universe. They are:

which is derived from the 00 component of Einstein's field equations, and

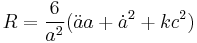

which is derived from the trace of Einstein's field equations.  is the Hubble parameter, G, Λ, and c are universal constants (G is Newton's gravitational constant, Λ is the cosmological constant, c is the speed of light in vacuum). k is constant throughout a particular solution, but may vary from one solution to another. a, H, ρ, and p are functions of time.

is the Hubble parameter, G, Λ, and c are universal constants (G is Newton's gravitational constant, Λ is the cosmological constant, c is the speed of light in vacuum). k is constant throughout a particular solution, but may vary from one solution to another. a, H, ρ, and p are functions of time.  is the spatial curvature in any time-slice of the universe; it is equal to one-sixth of the spatial Ricci curvature scalar R since

is the spatial curvature in any time-slice of the universe; it is equal to one-sixth of the spatial Ricci curvature scalar R since  in the Friedmann model. There are two commonly used choices for a and k which describe the same physics:

in the Friedmann model. There are two commonly used choices for a and k which describe the same physics:

- k = +1, 0 or -1 depending on whether the shape of the universe is a closed 3-sphere, flat (i.e. Euclidean space) or an open 3-hyperboloid, respectively.[3] If k = +1, then

is the radius of curvature of the universe. If k = 0, then a may be fixed to any arbitrary positive number at one particular time. If k = -1, then (loosely speaking) one can say that i·a is the radius of curvature of the universe.

is the radius of curvature of the universe. If k = 0, then a may be fixed to any arbitrary positive number at one particular time. If k = -1, then (loosely speaking) one can say that i·a is the radius of curvature of the universe. - a is the scale factor which is taken to be 1 at the present time.

is the spatial curvature when

is the spatial curvature when  (i.e. today). If the shape of the universe is hyperspherical and

(i.e. today). If the shape of the universe is hyperspherical and  is the radius of curvature (

is the radius of curvature ( in the present-day), then

in the present-day), then  . If

. If  is positive, then the universe is hyperspherical. If

is positive, then the universe is hyperspherical. If  is zero, then the universe is flat. If

is zero, then the universe is flat. If  is negative, then the universe is hyperbolic.

is negative, then the universe is hyperbolic.

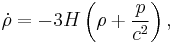

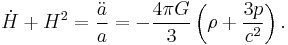

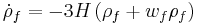

Using the first equation, the second equation can be re-expressed as

which eliminates  and expresses the conservation of mass-energy.

and expresses the conservation of mass-energy.

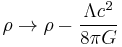

These equations are sometimes simplified by replacing

to give:

And the simplified form of the second equation is invariant under this transformation.

The Hubble parameter can change over time if other parts of the equation are time dependent (in particular the mass density, the vacuum energy, or the spatial curvature). Evaluating the Hubble parameter at the present time yields Hubble's constant which is the proportionality constant of Hubble's law. Applied to a fluid with a given equation of state, the Friedmann equations yield the time evolution and geometry of the universe as a function of the fluid density.

Some cosmologists call the second of these two equations the Friedmann acceleration equation and reserve the term Friedmann equation for only the first equation.

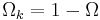

Density parameter

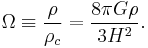

The density parameter,  , is defined as the ratio of the actual (or observed) density

, is defined as the ratio of the actual (or observed) density  to the critical density

to the critical density  of the Friedmann universe. The relation between the actual density and the critical density determines the overall geometry of the universe. In earlier models, which did not include a cosmological constant term, critical density was regarded also as the watershed between an expanding and a contracting Universe.

of the Friedmann universe. The relation between the actual density and the critical density determines the overall geometry of the universe. In earlier models, which did not include a cosmological constant term, critical density was regarded also as the watershed between an expanding and a contracting Universe.

To date, the critical density is estimated to be approximately five atoms (of monatomic hydrogen) per cubic metre, whereas the average density of ordinary matter in the Universe is believed to be 0.2 atoms per cubic metre.[4] A much greater density comes from the unidentified dark matter; both ordinary and dark matter contribute in favor of contraction of the universe. However, the largest part comes from so-called dark energy, which accounts for the cosmological constant term. Although the total density is equal to the critical density (exactly, up to measurement error), the dark energy does not lead to contraction of the universe but rather accelerates its expansion. Therefore, the universe will expand forever.

An expression for the critical density is found by assuming Λ to be zero (as it is for all basic Friedmann universes) and setting the normalised spatial curvature, k, equal to zero. When the substitutions are applied to the first of the Friedmann equations we find:

The density parameter (useful for comparing different cosmological models) is then defined as:

This term originally was used as a means to determine the spatial geometry of the universe, where  is the critical density for which the spatial geometry is flat (or Euclidean). Assuming a zero vacuum energy density, if

is the critical density for which the spatial geometry is flat (or Euclidean). Assuming a zero vacuum energy density, if  is larger than unity, the space sections of the universe are closed; the universe will eventually stop expanding, then collapse. If

is larger than unity, the space sections of the universe are closed; the universe will eventually stop expanding, then collapse. If  is less than unity, they are open; and the universe expands forever. However, one can also subsume the spatial curvature and vacuum energy terms into a more general expression for

is less than unity, they are open; and the universe expands forever. However, one can also subsume the spatial curvature and vacuum energy terms into a more general expression for  in which case this density parameter equals exactly unity. Then it is a matter of measuring the different components, usually designated by subscripts. According to the ΛCDM model, there are important components of

in which case this density parameter equals exactly unity. Then it is a matter of measuring the different components, usually designated by subscripts. According to the ΛCDM model, there are important components of  due to baryons, cold dark matter and dark energy. The spatial geometry of the universe has been measured by the WMAP spacecraft to be nearly flat. This means that the universe can be well approximated by a model where the spatial curvature parameter

due to baryons, cold dark matter and dark energy. The spatial geometry of the universe has been measured by the WMAP spacecraft to be nearly flat. This means that the universe can be well approximated by a model where the spatial curvature parameter  is zero; however, this does not necessarily imply that the universe is infinite: it might merely be that the universe is much larger than the part we see. (Similarly, the fact that Earth is approximately flat at the scale of a region does not imply that the Earth is flat: it only implies that it is much larger than this region.)

is zero; however, this does not necessarily imply that the universe is infinite: it might merely be that the universe is much larger than the part we see. (Similarly, the fact that Earth is approximately flat at the scale of a region does not imply that the Earth is flat: it only implies that it is much larger than this region.)

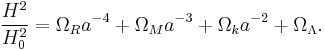

The first Friedmann equation is often seen in a form with density parameters.

Here  is the radiation density today (i.e. when

is the radiation density today (i.e. when  ),

),  is the matter (dark plus baryonic) density today,

is the matter (dark plus baryonic) density today,  is the "spatial curvature density" today, and

is the "spatial curvature density" today, and  is the cosmological constant or vacuum density today.

is the cosmological constant or vacuum density today.

Useful solutions

The Friedmann equations can be solved exactly in presence of a perfect fluid with equation of state

where  is the pressure,

is the pressure,  is the mass density of the fluid in the comoving frame and

is the mass density of the fluid in the comoving frame and  is some constant.

is some constant.

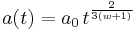

In spatially flat case (k = 0), the solution for the scale factor is

where  is some integration constant to be fixed by the choice of initial conditions. This family of solutions labelled by

is some integration constant to be fixed by the choice of initial conditions. This family of solutions labelled by  is extremely important for cosmology. E.g.

is extremely important for cosmology. E.g.  describes a matter-dominated universe, where the pressure is negligible with respect to the mass density. From the generic solution one easily sees that in a matter-dominated universe the scale factor goes as

describes a matter-dominated universe, where the pressure is negligible with respect to the mass density. From the generic solution one easily sees that in a matter-dominated universe the scale factor goes as

matter-dominated

matter-dominated

Another important example is the case of a radiation-dominated universe, i.e., when  . This leads to

. This leads to

radiation dominated

radiation dominated

Note that this solution is not valid for domination of the cosmological constant, which corresponds to an  . In this case the energy density is constant and the scale factor grows exponentially.

. In this case the energy density is constant and the scale factor grows exponentially.

Solutions for other values of k can be found at Tersic, Balsa. "Lecture Notes on Astrophysics". http://nicadd.niu.edu/~bterzic/PHYS652/PHYS652_notes.pdf. Retrieved 20 July 2011..

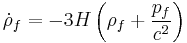

Mixtures

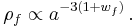

If the matter is a mixture of two or more non-interacting fluids each with such an equation of state, then

holds separately for each such fluid f. In each case,

from which we get

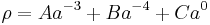

For example, one can form a linear combination of such terms

where: A is the density of "dust" (ordinary matter, w=0) when a=1; B is the density of radiation (w=1/3) when a=1; and C is the density of "dark energy" (w=−1). One then substitutes this into

and solves for a as a function of time.

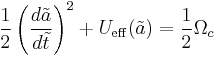

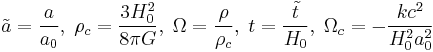

Rescaled Friedmann equation

Set  , where

, where  and

and  are separately the scale factor and the Hubble parameter today. Then we can have

are separately the scale factor and the Hubble parameter today. Then we can have

where  . For any form of the effective potential

. For any form of the effective potential  , there is an equation of state

, there is an equation of state  that will produce it.

that will produce it.

See also

Notes

- ^ Friedman, A (1922). "Über die Krümmung des Raumes". Z. Phys. 10 (1): 377–386. Bibcode 1922ZPhy...10..377F. doi:10.1007/BF01332580. (German) (English translation in: Friedman, A (1999). "On the Curvature of Space". General Relativity and Gravitation 31 (12): 1991–2000. Bibcode 1999GReGr..31.1991F. doi:10.1023/A:1026751225741.)

- ^ Friedmann, A (1924). "Über die Möglichkeit einer Welt mit konstanter negativer Krümmung des Raumes". Z. Phys. 21 (1): 326–332. Bibcode 1924ZPhy...21..326F. doi:10.1007/BF01328280. (German) (English translation in: Friedmann, A (1999). "On the Possibility of a World with Constant Negative Curvature of Space". General Relativity and Gravitation 31 (12): 2001–2008. Bibcode 1999GReGr..31.2001F. doi:10.1023/A:1026755309811.)

- ^ Ray A d'Inverno, Introducing Einstein's Relativity, ISBN 0-19-859686-3.

- ^ Rees, M., Just Six Numbers, (2000) Orion Books, London, p. 81, p. 82